Overview

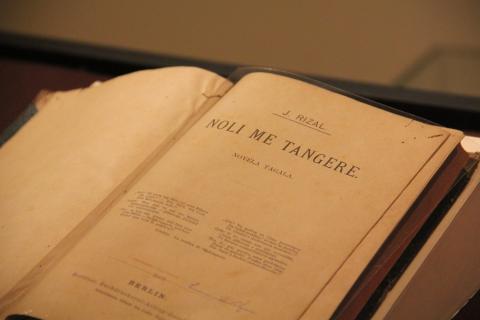

Since the publication of Jose Rizal’s Noli Me Tángere (The Social Cancer) in 1887, the character of Maria Clara has become synonymous with Philippine culture. Throughout the years, she has been deified and idolized, representing

the values that a Filipina woman should uphold and the standards to which she should adhere. As such, she has acted as the subject for many literary analyses. From simply being Rizal’s heroine, she has subsequently transformed into an archetype, the model Filipina.

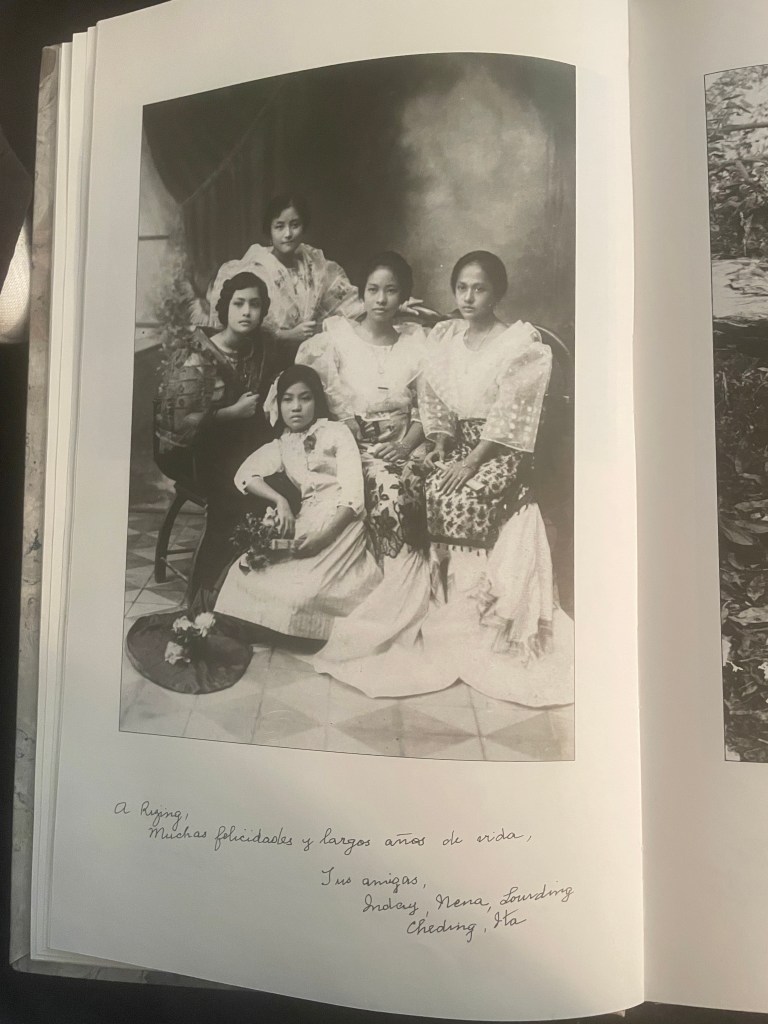

What, or rather, who is the model Filipina? Firstly, it is important to note that “achieving” Maria Clara is impossible. Her actions are fiercely contested. While some scholars view her as a static damsel in distress, waiting to be saved by dynamic hero Crisostomo Ibarra, others argue that she was obligated to exist within the confines of a Spanish patriarchal society. (It would be remiss not to mention that the bourgeois Rizal created Maria Clara according to the male gaze; his former lover, Leonor Rivera, is thought to be the inspiration for the iconic female heroine.) Typically, we see her as the overly emotional, dutiful, pious, silent, and martyr-like figure that was the object of Ibarra, Dámaso, and Salvi’s attentions. She is said to represent the colonial, exploitative relationship between Spain and the Philippines. With this claim, our perceptions of her start to become complex. As a wealthy mestiza, she is a member of the privileged elite. Seemingly, she is the enemy. Her innocence and virtuosity follow the sexist Spanish model that women must be submissive towards men. Whatsmore, she might even be interpreted as the enemy, as she betrays Ibarra by giving a letter critiquing the current imperial system to Father Salvi in exchange for a letter exposing her as the illegitimate child of Father Dámaso. However, others argue that the pressure to make the ethical choice and the alleged “protection” that Spain could provide reflect the political conflict in the country, thus absolving Maria Clara of her decision. Instead of viewing her as an individual in need of saving, perhaps we should situate her in history. As a woman in the colonial Philippines, she possesses very few options. Her parentage (being born in wedlock, which the letter reveals that she was not), social class, and race culminate in her candidacy for marriage. Although she was set to marry Ibarra, his disgraced position necessitates the rupture of their courtship. Wanting the best for his daughter, Captain Tiago (adopted father) and Father Dámaso (biological father) encourage her to marry a peninsular Spaniard. However, she refuses to marry and gives the priest an ultimatum: enter a convent or commit suicide. Reluctantly, she is granted permission and spends the rest of her life in the Royal Monastery of Saint Clare.

Several arguments can be made about her agency in Noli and Fili, but if there is one key takeaway from Maria Clara’s tale is the political nature of her character. In understanding the more than three century long Spanish occupation of the Philippines, we must take advantage of reading and even empathizing with Maria Clara. Regardless of the various identities that she was and is assigned, she is intended to elicit responses, becoming more of an open-ended character as the years pass.

A crucial aspect of Philippine heritage, she represents colonial (mestiza) beauty standards that still live on today as well as the fabricated glamor and genuine tragedy of the past. Indeed, she is a model, though constantly cast and recast in differing lights depending on the author and audience. Some may call this innocent provinciana a hero or a victim. How does this quintessential Filipina exist in our imaginations?

Forever a pillar in the womxn’s literature canon, we are able to use her story when reading the texts in this course. The womxn of these texts either act in accordance with Maria Clara’s casting or try to defy it, or maybe somewhere in between. As we embark upon this challenge to determine the “making” of the Filipina woman, we first must look to her, or rather to history, on themes of womanhood, femininity, race, Catholic influence, and class. In a way, she is everyone’s daughter, perpetually a young woman whose fate unravels in front of the nation’s eyes.

Sisa, the Woman in the Shadows:

The other female protagonist in Rizal’s novels is Sisa. Sisa and Maria Clara were intended to be FOILs, or literary opposites. She represents the reality of many impoverished Filipinos who were oppressed by the Spanish. While Maria Clara is the pure, wealthy virgin who is admired by all, Sissa lives in an abusive environment, harassed by her husband, the Church, and the Spanish penal system. Throughout Noli, her husband emotionally abuses her and beats her. However, she remains kind, patient, and loving towards her children. Upon hearing of her son Crispín’s death at the hands of the curate, she is driven to insanity. The Guardia Civil misinterprets her grief and further abuses her until her death a few days later. In the novel, we might view her as a martyr, innocently dying at the hands of Spanish tyranny.

As Maria Clara’s “other half”, it is important to analyze her through lenses of race, class, and motherhood. Unlike her virgin counterpart, Sisa is a devoted mother to two sons subjected to the Church’s bureaucratic cruelty. What role does motherhood play in the fight for independence? How do race and class influence one’s treatment as a woman? How has Sisa, like Maria Clara, contributed to the “making” of the Filipina woman?