Ecofeminism

| Supporting Sources: Postcolonial Ecofeminism Women and Nature: An Ecofeminist Reading of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus Postcolonial Literature and Ecofeminism Ecofeminism is a theory that argues that capitalism has created a dangerous patriarchal divide between nature and culture, often citing Western anthropological values of modernity. Ecofeminists in the 1970s argued that within this divide, women are often the victims. With gendered references such as “Mother Nature” among many of the feminizations of the natural landscape, scholars have argued that women are intrinsically “natural” due to their intimate ability to care and provide for others, just as nature has done for millenia. Riddled with binaries, this theoretical framework hopes to deconstruct the division between humans and the earth. |

“Sampaguita Song” by Marjorie Evasco

- How does Evasco utilize the flower motif to narrate her childhood? How do her perspectives of her childhood differ from the beginning of her poem to the end?

- How does Evasco praise and pity the Sampaguita flower seller? Using ecofeminism, how can we analyze the lines: “Flowers are hard to sell / Entwined thus with your poverty / They wilt your eyes, dust and soot.”?

- Nature is often a proxy for memory. How are women described as the bearers of stories as well as nature in this poem?

- How do you interpret the last words “For Buena Mano” in the poem? Is this a case of irony? Why or why not?

The Creation Story

| Supporting Sources: The Aswang Project Creation Myths from the Philippines |

“Triptych” by Shirley Ancheta

- How does Ancheta describe the origins of the universe? How does her description differ from previous tales?

- To whom is she speaking? Who is her audience? What role do the pronouns “she” and “us” play in declaring female agency in The Creation Story?

- Why do you think Ancheta used “Triptych” as the title? How can we see the religious synergism between Catholicism and pre-colonial religion?

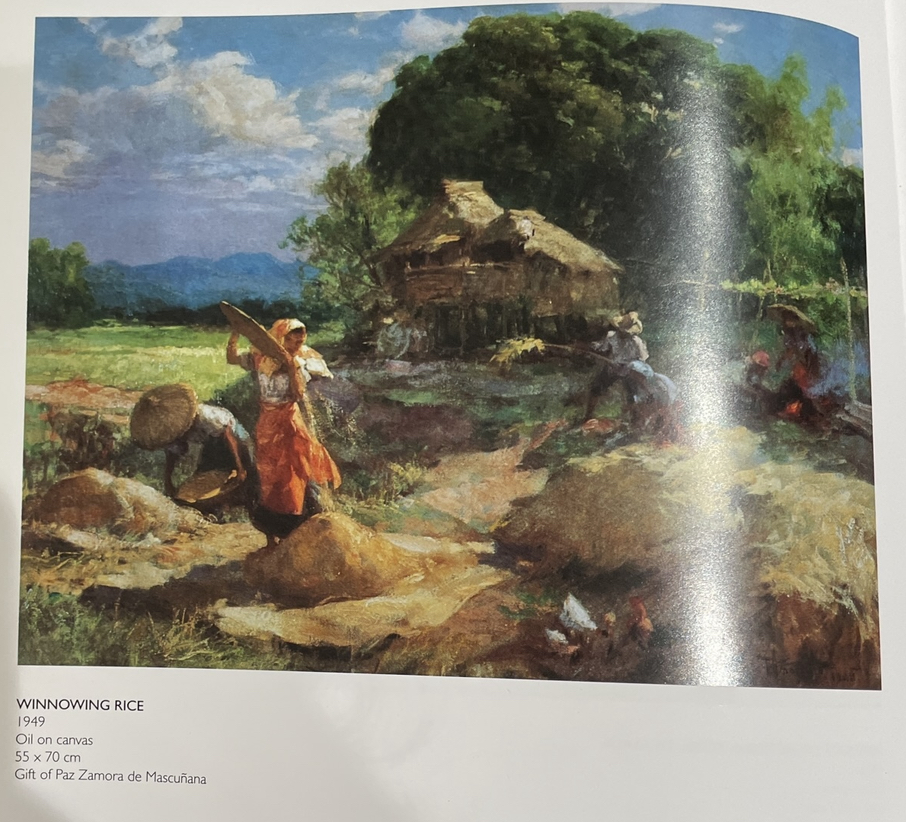

The (Colonial) Male Gaze

“The Feast of Death” by Buenaventura Rodriguez

- What examples of orientalism can we see in Rodriguez’s work? How does he equate women with the overall Philippine landscape? Are women part of the landscape or the landscape itself?

- How does Rodriguez’s romantic style of writing fit in with the political context of the time period? (Think about Rizal’s descriptions of Maria Clara.)

- Analyzing the following passage: “But she who did not know the decency in laces nor in the magnificent dresses made for vanity’s sake and which at times end up stained with infamy and disgrace, believed that her best ornaments were the curls of her black hair that adorned her fragrant shoulders, her extremely dark eyes. In short, all the assets of her body seemed to have been made for the joy of that burning beach, of that dark body which was the sacred coffer where the sun of the warm afternoon kept the gold of its rays.” What claims does the author make about the Westernization of customs? Is he in favor of them? Does he believe that humans and nature can co-exist?

- How does Rodriguez sexualize nature?

Nature as Memory

“Cartographer” by Conchitina R. Cruz

- What is the significance of the title “Cartographer”? What connection can we make between the title and the Philippines’ colonial history?

- How does Cruz explore the relationship between space and the human body? What does she claim about our intimacy with nature? (Use the quote: “I am small, a landscape defined by the space within your arms.” as a guide during discussion.)

- How can we understand “territory” in this poem, with Cruz writing “You think the only earth is skin, coloring me with your kiss, marking territory”?

- How does Cruz create distance, both physically and metaphorically, using the “you” and “me” pronouns in her poem?

| Thematic Questions: 1) Three out of the four works presented in this section are written by women. How do their perspectives differ from that of Rodriguez? 2) What thematic commonalities do we see throughout all four works? |