Overview

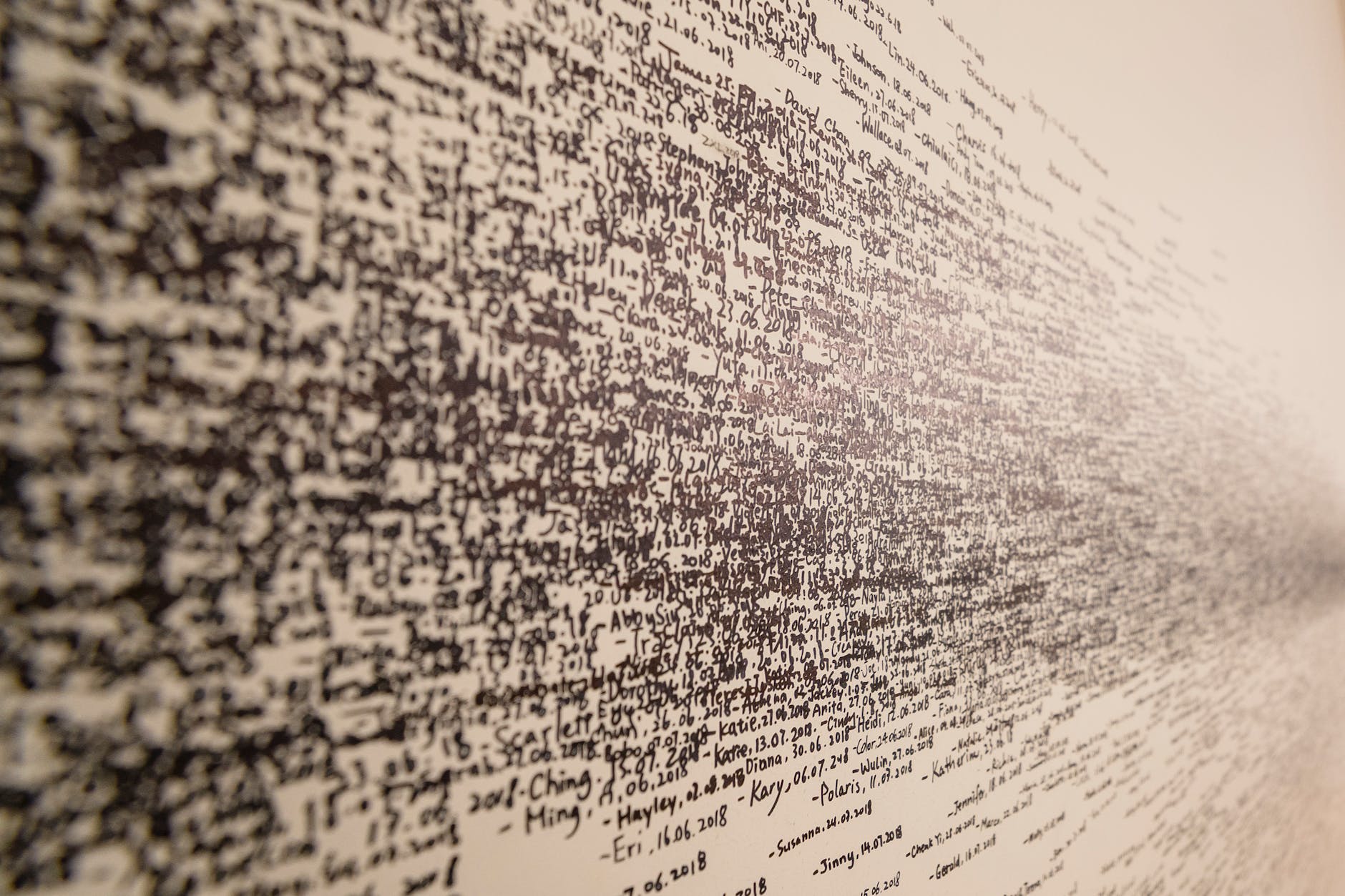

Much of our identity comes from language. Through language, we can understand the stories of our past and tell the realities of our present. Yet language, although it has superficially been considered just a vehicle through which we understand each other, presents an intricate web of sociocultural politics. There is an ideology behind language usage. In the Philippines, this ideology is particularly evident. The country, by nature of colonization, is multilingual. Many people know their vernacular language (their native regional language) as well as English. As history demonstrates, English (and Spanish before that) was an indicator of success. One’s class was highly dependent on their ability to speak English. In this case, it is through language that we may understand race and class in the Philippines.

Before the United States colonized the Philippines, Spain was the ruling government. Spanish was the language of the elite: the mestizos, Philippine-born Spaniards, and the peninsular Spaniards. Fluency in Spanish indicated that a person was one of these three: well-educated, respected, and wealthy. When the U.S. invaded, they forced everyone, regardless of their race and class, to learn English. However, the individuals who became the most fluent, due to education and access to resources, were those in power previously. Therefore, power mostly remained in the same hands, with the attitude towards the colonizing language being the same.

Language and identity are sisters. High literacy in English became associated with being a member of the upper class while having “broken English” was a characteristic of the lower classes. Here, we begin to have just a glimpse of the polarizing power of language. We see a binary start to emerge: the urban versus the provincial, the oral history versus the written history, the colonizer versus the colonized. It is important to realize that language has the ability of perpetuating racist ideologies. For example, although many Filipinos speak English (the U.S. believing that English would make Filipinos into model citizens), some speak with an accent, one that is frequently made fun of and berated. Despite speaking fluently, they will speak like their colonizers, which leads the U.S. to consider them “behind” (Rafael 56).

The U.S. is so willing to believe that English is theirs. Nevertheless, once Filipinos began to use English to tell their own stories, they took back agency. While this is a remarkably one-dimensional way of viewing sociolinguistics in the Philippines, it partially explains the type of literature that we’ve seen throughout this course, leading us to ask ourselves: Can English be Filipino?

The Philippines’ relationship with English has always been complicated. Prioritizing English caused the suppression of vernacular languages. English in the Philippines was still foreign, and vernacular tongues were forced to be forgotten (Rafael 48). As much as language could be a sign of nationhood and unity, it could also be weaponized. English was used to create a hierarchy. Yet, as more and more people learn the language (which has its own nefarious neocolonial issues), individuals unite for a common cause. Some of the literature in this course is written by Filipino Americans. It is perhaps through them where language-identity and agency in expression/translation can change. Beyond seeing language as an aesthetic, we can use this course as an opportunity to closely examine the usage of language in literature, beginning with the texts in this section.

——-

Supplementary Sources:

Nationalism, Imagery, and the Filipino Intelligentsia in the Nineteenth Century

Linguistic Currencies: The Translative Power of English in the United States and Southeast Asia

Motherless Tongues: The Insurgency of Language amid Wars of Translation by Vicente Rafael